- Home

- About Us

- Jurisdiction

- Committee Membership

- Subcommittee Assignments

- Capital Markets

- Financial Institutions

- Housing and Insurance

- National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions

- Digital Assets, Financial Technology, and Artificial Intelligence

- Oversight and Investigations

- Task Force on Monetary Policy, Treasury Market Resilience, and Economic Prosperity

- Committee Rules

- Committee Reports

- Budget Views

- Oversight Plan

- News

- Committee Events

- Consumer Help

- CONTACT

DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION: HOLDING AMERICA’S LARGE BANKS ACCOUNTABLE

Banks and other financial services firms claim to agree with the underlying premise that diverse, inclusive organizations can be more profitable and productive. But despite the known benefits, the financial services industry, including our nation’s banks, remains mostly white and male. This is not only true of banks’ workforces and executive ranks, but is also true for banks’ boards of directors, suppliers, and asset managers. There is little relevant data in this space because banks and other financial services firms do not fully disclose their diversity and inclusion data or policies. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) created the Offices of Minority and Women Inclusion (OMWI) in part to begin to hold industry accountable for diversity and inclusion. Despite this explicit authority, the prudential regulators, including the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), issued guidance (known as the Joint Standards) that permits banks and other institutions to comply with the OMWIs’ requests for diversity and inclusion data voluntarily. Since the adoption of the Joint Standards, banks have only marginally participated in requests from the OMWIs. Further, the little data that is collected is not publicly available.

Despite these shortcomings, the Committee staff analyses also found that some banks are implementing diversity-focused policies and practices including:

The Committee staff analyses also found that:

While all 44 banks acknowledged in some way that they need to improve with respect to diversity and inclusion, nearly half of the banks surveyed did not share any specific challenges in implementing their diversity and inclusion goals. For those banks that identified challenges, the most prevalent challenges reported were:

To ensure full compliance with the original intent of Section 342 of the Dodd-Frank Act and to increase transparency into banks’ diversity and inclusion results, Congress should consider the following legislative actions to improve diversity and inclusion at America’s largest banks:

IMPORTANCE OF DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION IN FINANCIAL SERVICES

Diversity and inclusion are key business imperatives. In May 2019, the Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion convened a hearing entitled “Good for the Bottom Line: A Review of the Business Case for Diversity,” at which a panel of experts emphasized that inclusive organizations are more productive and profitable. Numerous studies have validated the benefits of diversity and inclusion within an organization, including:

PURPOSE OF BANK DIVERSITY DATA REQUEST

Diversity data is important to measuring the success of diversity and inclusion outcomes. Despite organizations’ best intentions, without data, they will be unable to evaluate and effectively implement their diversity and inclusion goals. Organizations must track talent acquisition, promotions, pay, and employee perceptions to understand the impact of their diversity initiatives. Accordingly, lawmakers included provisions in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) to promote diversity and inclusion in the financial services industry, including the collection of diversity data.[4] Specifically, Section 342(e) of the Dodd-Frank Act established and requires the Offices of Minority Women and Inclusion (OMWI) to submit an annual report to Congress regarding the actions taken by the respective financial services agencies and the OMWI office, which shall include:[5]

Unfortunately, OMWI directors may face challenges preparing their annual reports because industry participation in sharing diversity data and policies is still voluntary. The Joint Standards for Assessing the Diversity Policies and Practices of Entities Regulated (Joint Standards) were adopted by the financial services regulatory agencies in June 2015.[6] In a March 2019 letter to the OMWI directors, Diversity and Inclusion Subcommittee Chair Beatty expressed her continued concern with industry’s voluntary compliance with the Joint Standards and voluntary participation in sharing diversity data and policies with OMWIs: Other congressional Democrats and I responded in disdain to the agencies’ draft [Joint Standards] and urged that the final standards for all regulated entities include: (1) mandatory diversity assessments and disclosures; (2) information on both workforce and supplier diversity practices and policies; and (3) requirements for public disclosure of diversity data. The final rule still did not meet these expectations, which were set forth because data and transparency are so very essential in measuring the success of diversity initiatives. Full implementation of the letter and spirit of Section 342 may never be accomplished if OMWIs still struggle with the basic need to gather diversity data from industry and lack support from their agency leaders.[7] After the megabank CEOs testified before the Financial Services Committee in April 2019, Chair Beatty asked them to more specifically share information on their banks’ diversity and inclusion data and practices. Chairwoman Waters and Chair Beatty subsequently expanded that request to all bank holding companies and savings and loan holding companies with assets over $50 billion. In keeping with diversity information that would also be requested annually by OMWIs, a total of 44 banks were asked to respond to the following diversity related questions:

The full text of the request letter that was sent to the 44 banks can be found in appendix I. See Table 1 for a list of banks that received the Committee’s request by asset size. Committee staff’s detailed methodology and report definitions can be found in appendices II and III, respectively. Table 1: America’s Largest Banks by Asset Size[8]

COMMITTEE STAFF FINDINGS ON BANK DIVERSITY AND INCLUSIONWORKFORCE DIVERSITY

Research shows that diverse workforces bring higher productivity and profitability. During an April 2019 hearing entitled, “Good for the Bottom Line: A Review of the Business Case for Diversity,” the Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion examined the benefits of workforce diversity, including:

Unfortunately, biases against women and underrepresented minorities perpetuate the lack of gender, racial, and ethnic diversity within the financial services industry, including at banks and in their senior ranks. In 2019, the New York Times reported on discriminatory practices towards black employees and customers in the banking industry, noting that “it’s no secret that racism has been baked into the American banking system.”[11] The article described the accounts of a Black employee and a Black customer who experienced discrimination at one of the nation’s leading banks and noted that several large banks had recently paid restitution to Black employees for cutting them off from career opportunities. In its 2017 review of diversity trends in financial services, GAO similarly indicated that “unconscious bias is an issue that can negatively affect women and minorities” in hiring and promotion practices.[12] Expert witnesses appearing before the Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion in October 2019 also emphasized that when these types of biases limit opportunities, underrepresented employees move out when they do not see a path to move up.[13] Moreover, one witness testified that to overcome the effect of and remove biases, banks and other institutions must intentionally enhance their diversity and inclusion efforts, including the development, retention and promotion of diverse talent.[14] Committee Staff Findings on Bank Workforce Diversity:

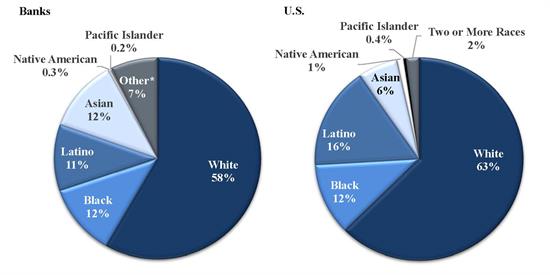

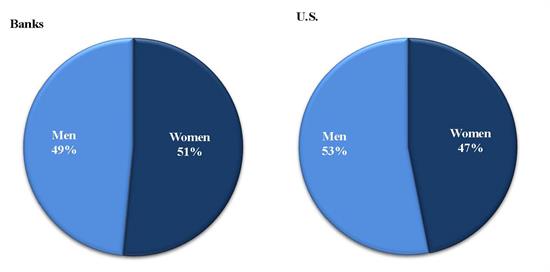

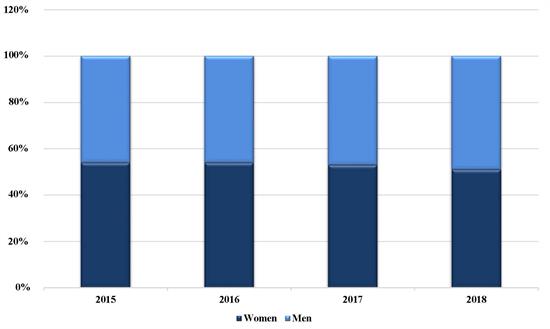

Committee staff analysis revealed that although the workforce diversity demographics of the nation’s largest banks appear to align with the composition of the U.S. labor force, bank workforce diversity is more visible in entry level rather than executive and senior level positions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bank |

Year |

Employment Level |

Female |

Racial/Ethnic Minority |

|

Ally Bank |

2019 |

Executive/Senior Level Officials and Managers (1A & 1B) |

26.6% |

11.5% |

|

BB&T |

2017 |

Executive |

26.0% |

05.8% |

|

Capital One |

2018 |

Executive, Senior Officials, Managers |

28.1% |

19.4% |

|

Charles Schwab |

2019 |

Officers |

31.8% |

14.5% |

|

Citi Bank |

2018 |

Global Managing Directors & Directors/US Ethnic Diversity |

25.0% |

28.0% |

|

Citizens |

2018 |

Executive Senior Level & Managers |

48.0% |

15.0% |

|

Comerica |

2018 |

Executive Senior Level & Managers |

22.2% |

11.1% |

|

Credit Suissee |

2018 |

Managing Director |

16.0% |

29.0% |

| Deutsche Bank | 2018 | Executive/Senior Levels & First Mid Officials and Managers | 25.8% | 29.1% |

|

Fifth Third |

2018 |

Executive Senior Level & Managers |

25.2% |

11.2% |

|

Goldman Sachs-U.S. Workforce |

2018 |

Executive, Senior Officials, Managers |

23.0% |

21.9% |

|

HSBC |

2018 |

Executive and Senior Management |

25.4% |

23.8% |

| Huntington | 2019 | Diverse Managers and Executives | 43%[18] | |

|

Morgan Stanley |

2018 |

Executive Senior Officers & Managers |

17.8% |

16.9% |

|

MUFG |

2018 |

Senior Executives and Managers |

18.0% |

38.4% |

|

Northern Trust-Global Workforce |

2018 |

Executive/Senior Management |

43.6% |

13.3% |

|

PNC Financial |

2018 |

Senior Level |

22.4% |

12.5% |

|

RBC |

2018 |

Executives |

27.0% |

15.0% |

|

State Farm |

2018 |

Executives |

38.7% |

22.2% |

|

State Street |

2018 |

Executives/Senior Level Officials and Managers |

28.8% |

14.7% |

|

Sun Trust |

2018 |

Executives/ Managers |

50.9% |

32.2% |

|

US Bancorp |

2018 |

Executive/Senior Levels Officials and Managers |

31.1% |

10.2% |

|

UBS |

2018 |

Executive/Senior Officials & Managers |

15.2% |

12.0% |

|

Wells Fargo |

2018 |

Executive/Senior Levels & First Mid Officials and Managers |

50.3% |

33.3% |

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

BOARD DIVERSITY

Board diversity has been inextricably linked to a company’s competitiveness. In her opening statement at a hearing on this topic, Chairwoman Waters noted that “Diversity is one of the best investments a company can make. Diverse boards help intentionally guide companies and industry toward business solutions that maximize returns on that diversity investment.”[19] Below are examples of the importance that were highlighted during this hearing:[20]

- Board diversity enhances competitiveness: T. Rowe Price noted in its 2018 proxy voting guidelines that “boards lacking diversity represent a suboptimal composition and potential risk to company’s competitiveness over time.”[21]

- Board diversity improves innovation: Over 90 percent of companies that participated in Deloitte’s 2017 board diversity survey agreed that increased board diversity will improve their companies’ ability to innovate as well as their overall business performance.[22]

- Board diversity increases performance and profits: After analyzing the performance of approximately 90 U.S. bank holding companies, two Federal Reserve economists also concluded that banks with more gender diversity on their boards (those with a female share of about 13 to 17 percent) perform better.[23] Moreover, they suggested that “banks' continued voluntary expansion of board gender diversity is likely to bring performance benefits, provided that the banks are well-managed or capitalized.”[24] Companies with three or more women on their boards also saw even more financial benefits, including higher average dividend payout ratios and return on equity.[25]

Committee Staff Findings on Board Diversity of America’s Large Banks:

Bank Board Seats Are Mostly Occupied by Whites and Males

Congressman Gregory Meeks (D-NY) Chair, Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Financial Institutions |

“” “In November 2019, the House of Representatives also made history when it passed legislation I sponsored to require public companies, including banks, to publicly disclose the gender, racial and ethnic composition of their corporate boards. Such disclosure will further hold banks accountable to have their boardrooms similarly reflect the diversity of America.” |

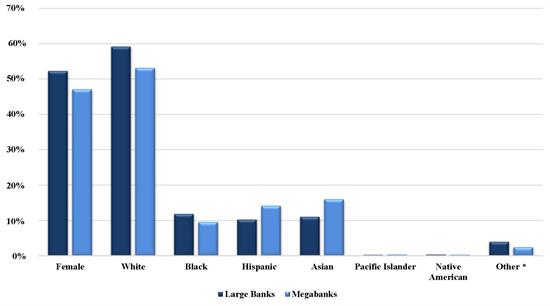

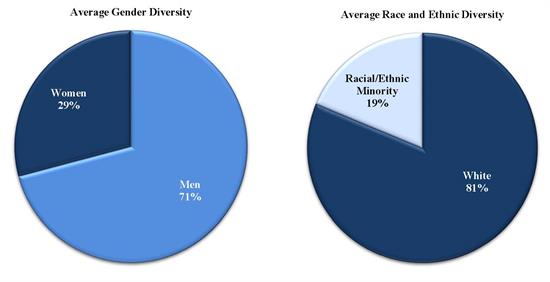

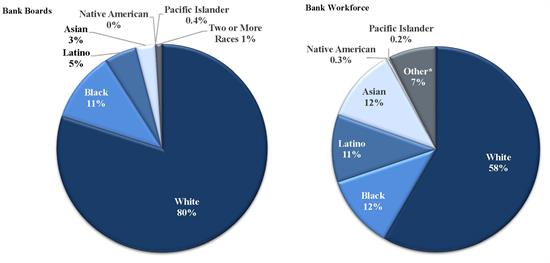

Seats on the boards of directors of America’s largest banks continue to be filled predominantly by white males. The Committee staff’s review of banks’ responses on their board diversity finds that the boards of large banks are an average of 80 percent white and 70 percent male, as shown in Figure 7. Specifically, the figure compares board diversity of the 8 megabanks and 34 other large banks that reported board diversity data by gender, race and ethnicity for 2018.

Figure 7. Comparison of Other Large Banks Versus Megabanks Board Diversity (Most Recent Year Reported)

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

Table 3 shows the extent to which banks provided requested board diversity demographics to the Committee. For the 43 banks that reported aggregated and disaggregated board diversity data, the table also shows the percentages of female and minority (all racial and ethnic minorities reported) directors.

Table 3: Banks Reporting Board Diversity Data Demographics (Most Recent Year Reported)

|

Bank Name |

Female Directors |

Minority Directors |

|

Ally Financial |

33.3% |

08.3% |

|

American Express |

18.2% |

27.3% |

|

Bank of America |

31.3% |

18.8% |

|

Barclays |

66.7% |

|

|

BB&T |

31.3% |

25.0% |

|

BBVA |

08.3% |

50.0% |

|

BMO |

45%[27] |

|

|

BNP |

21.4% |

14.3% |

|

BNY Mellon |

25.0% |

25.0% |

|

Capital One |

27.3% |

27.3% |

|

Charles Schwab |

No Data[28] |

|

|

Citigroup |

33.3% |

13.3% |

|

Citizens Bank |

25.0% |

08.3% |

|

Comerica |

25.0% |

25.0% |

|

Credit Suisse |

25.0% |

12.5% |

|

Deutsche Bank |

40.0% |

10.0% |

|

Discover |

27.3% |

09.1% |

|

ETRADE |

25.0% |

08.3% |

|

Fifth Third |

28.6% |

21.4% |

|

Goldman Sachs |

36.4% |

18.2% |

|

HSBC |

25.0% |

08.3% |

|

Huntington |

38.5% |

15.4% |

| JP Morgan | 18.2% | 18.2% |

|

Key Bank |

35.7% |

14.3% |

|

M&T |

11.1% |

11.1% |

|

Morgan Stanley |

30.8% |

23.1% |

|

MUFG |

27.3% |

36.4% |

|

Northern Trust |

23.1% |

38.5% |

|

NY Community Bancorp |

09.1% |

18.2% |

|

PNC |

30.8% |

23.1% |

|

RBC |

33.3% |

00.0% |

|

Regions |

23.1% |

30.8% |

|

Santander |

06.9% |

31.0% |

|

State Farm |

27.3% |

18.2% |

|

State Street |

25.0% |

08.3% |

|

SunTrust |

18.2% |

27.3% |

|

SVB |

27.3% |

09.1% |

|

Synchrony |

40.0% |

30.0% |

|

TD Bank |

18.2% |

18.2% |

|

TIAA |

38.7% |

32.3% |

|

UBS |

33.3% |

16.7% |

|

USAA |

28.6% |

21.4% |

| US Bancorp | 35.3% | 23.5% |

|

Wells Fargo |

23.1% |

23.1% |

Note: Because banks provided varying years of data, this analysis includes the most recent year reported by each bank

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

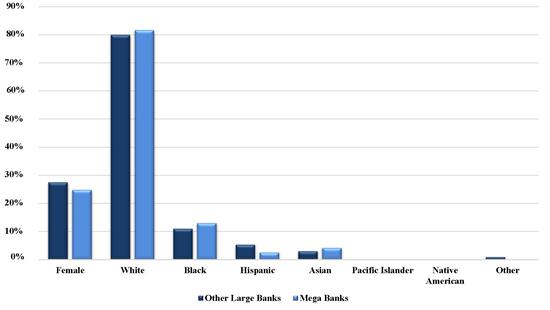

Banks’ reported board diversity generally did not match the diversity of banks’ workforce diversity, as shown in Figure 8. For example, although Committee staff analysis shows that Blacks comprise approximately 12 percent of banks’ workforce, they are represented in 11 percent of bank board seats. However, Latinos and Asians make up 11 percent of banks’ workforce and only five percent and three percent of banks’ board seats, respectively.

Figure 8. Comparison of Bank's Board and Workforce Diversity (Most Recent Year Reported)

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

SUPPLIER DIVERSITY

With increasing diverse population and business growth rates, industry groups that focus on supplier diversity have emphasized that corporations should increase their spending and investing with diverse customers and businesses in order to gain and maintain a long-term competitive advantage. In 2014, the National Minority Supplier Development Council, reported that minority-owned businesses generated $1 trillion in economic output to the U.S. economy, creating nearly 6 million American jobs.[29] Furthermore, the National LGBT Chamber of Commerce (NGLCC), a national advocacy organization dedicated to expanding economic opportunities for the LGBT business community, touts that LGBT-owned businesses generate over $1.7 trillion in economic impact, creating jobs and innovating business solutions for its members.[30] The Billion Dollar Roundtable, founded in 2001, was created to “recognize and celebrate corporations that achieved spending of at least $1 billion with minority- and woman-owned suppliers.”[31] As of January 2020, 2 of the 44 banks the Committee reviewed are members of the Billion Dollar Roundtable.[32]

Committee Staff Findings on Supplier Diversity:

Lack of Transparency About Banks’ Supplier Diversity Investments

Committee staff’s analysis of bank supplier diversity data was limited by a lack of data. Four of the 44 banks do not track their spending with diverse firms. Additionally, 15 of the 44 banks did not respond to the question or did not provide a quantifiable amount on diverse supplier spending, as shown in Table 4. For those banks that responded, on average, 8.9 percent is invested with diverse suppliers.

Table 4: Banks Reporting Supplier Diversity Data

|

Supplier Diversity Data |

||

|

|

Banks Reporting Supplier Diversity Data |

Banks Not Providing Quantifiable Information on Supplier Diversity |

|

Ally |

American Express |

|

|

TOTAL |

33 |

11 |

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

PAY EQUITY

Pay equity creates an inclusive and fair environment where employees receive equal pay for equal work regardless of gender, race or ethnicity. Studies validate that pay equity gaps for women and minorities versus their counterparts limit their ability to build wealth and experience full inclusiveness in the workplace. A 2017 report on closing the gender wealth gap estimated that income for all women is about 79 cents on the dollar and that disparity is even more substantial for women of color: 64 cents and 54 cents on the dollar for Black and Latina women, respectively.[33] Additionally, women tend to work in lower-paying job sectors and are more likely to be working part-time or discriminated against in the workplace because of caregiving duties compared to men, further reducing long term earnings potential.[34] Based on an analysis of Federal Reserve data, a 2019 McKinsey report suggested that “Black Americans can expect to earn up to $1 million less than White Americans over their lifetimes.”[35] To highlight how pay equity contributes to the racial and gender wealth gap, the Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion held a hearing in September 2019 entitled “Examining the Racial and Gender Wealth Gap in America” where several witnesses testified that improving data collection on the pay and wealth gap is essential to remedying disparities based on gender and race.[36]

Committee Staff Findings on Banks’ Pay Equity:

Congressman Wm. Lacy Clay (D-MO) Chair, Subcommittee on Housing, Community Development and Insurance |

“” “Even though the Committee staff’s report on bank diversity data shows that gender pay equity is improving, banks should publicly share more about their pay equity data to affirm their commitment to closing the wealth gap in America.”

|

Lack of Transparency About Banks’ Pay Equity Ratios

Although 27 of the 44 banks reported that they conduct an internal review of gender pay equity, 15 publicly disclose this information or provide transparency about their efforts to close the gap, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Banks Reporting Pay Equity Data

|

Banks Name |

|

|

Provided Pay Equity Data |

Ally Financial |

|

Did Not Provide Pay Equity Data |

Barclays |

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

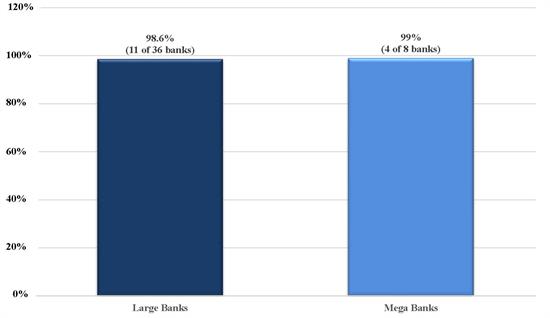

Of the four megabanks and 11 other large banks that provided pay equity data, Committee staff calculate that, on average, those banks have achieved an adjusted pay equity ratio of almost 99 percent, as shown in Figure 9. In lieu of responding to the question about pay equity, four banks said they planned to disclose employee compensation data via the next required annual filing with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) due September 30, 2019. Over half of banks said that they conduct an internal review on pay equity while 10 stated that they allow for an independent third-party review on this subject.

Figure 9. Comparison of Other Large Banks Versus Megabanks: Average Pay Equity

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

As an example of efforts to close the gender pay gap, Citigroup said that it annually releases to the public its pay equity data comparing compensation of women to men, and U.S. minorities to U.S. non-minorities. Citigroup reported that its gender pay equity ratio was 99 percent when adjusting for factors such as job function, level and geography. Further, among Citigroup’s U.S. employees, the company reported that people of color earn less than their White colleagues.

INVESTING WITH DIVERSE ASSET MANAGERS

Congressman Brad Sherman (D-CA) Chair, Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship, and Capital Markets |

“” “The Committee’s staff report on bank diversity data shows that America’s 44 largest banks similarly aren’t giving investment opportunities to diverse-owned firms and many aren’t tracking it all. Banks and other investors must make diversity a priority to overcome historic biases.”

|

Despite evidence that women and minority-owned firms perform as well as (and sometimes outperform) their industry counterparts, they are not consistently selected to manage institutional assets.[37] Although women and minority-owned firms account for approximately 8.6 percent of the asset management industry, recent reports show that they only manage 1.1 percent of all assets under management or $785 billion out of $71.4 trillion, and are underrepresented as managers in every asset class.[38] For example, in advance of a House Financial Services Committee October 2019 hearing on Facebook, the company indicated that it uses zero diverse asset managers to manage its $52 billion in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities.[39]

In June 2019, the Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion convened a hearing on diverse asset managers to further highlight these challenges and offer solutions to increase the presence of diverse asset management firms in the industry.[40] Experts and lawmakers discussed legislation aimed at promoting the increased consideration of diverse asset management firms by requiring companies registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission to consider at least one diverse asset manager when contracting out for investment advisor services and report to the agency.[41]

Diverse asset firms and brokers have expressed concerns about being excluded from investment opportunities in the market. In an April 2019 roundtable hosted by the Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion, diverse asset management and broker dealer firms discussed how unconscious biases against diverse firms and a lack of intentionality to work with them have limited their ability to increase their assets under management. Further, the diverse asset management firms said that they have been labeled as “riskier,” and therefore, have more hurdles to overcome with potential clients.

Committee Staff Findings on Banks’ Investment with Diverse Asset Managers:

Tracking and Investing with Diverse Asset Mangers is Not a Bank Priority

America’s largest 44 banks generally do not track or prioritize investing with diverse asset management firms. Four banks reported that they do not track investments with diverse asset firms.[42] Unfortunately, most banks did not provide full responses to the Committee’s questions about the amounts managed by diverse firms for their asset management, 401(k), wealth management investments, and underwriting as shown in Table 6.

Table 6: Banks and Diverse Management Firms

|

|

Investment with Asset Management Firms |

Investment with Retirement Plans |

Investment with Wealth Management Firms |

Investment with Underwriters |

|

Banks Reporting Number of and/or Amounts Invested in Diverse Firms [43] |

Ally Financial BNY Mellon Capital One Citigroup Citizens Bank Comerica Credit Suisse

Morgan Stanley PNC RBC Regions Santander State Street Sun Trust SVB TIAA† UBS USAA† Wells Fargo |

Charles Schwab |

American Express† |

Ally Financial |

|

Banks Not Reporting Quantifiable Information |

BNP |

Ally Financial |

Ally Financial |

Bank of America |

Note: *Note: “Not Reporting Quantifiable Information” refers to banks that do not track or did not provide an amount invested with diverse firms in each category.

†These banks reported that they do not have funds invested in a particular line of business or do not use third party investment firms or underwriters.

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

Of the six banks that responded to the question about 401(k) and retirement plan assets invested with diverse managers, the data shows that diverse asset management firms manage an average of 8.9 percent of all the banks’ externally managed 401(k) investments. Similarly, of the 11 banks that provided data on externally managed wealth management, the average percentage invested with diverse asset managers was 6.9 percent of the banks’ externally managed wealth dollars. Only six banks responded with the percentage transacted through diverse-owned underwriters. Of these six banks, the average percentage transacted through diverse broker dealers was 2.9 percent.

DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION PRACTICES AND POLICIES

Committee Staff Findings on Banks’ Diversity and Inclusion Practices and Policies:

To build and maintain a diverse and inclusive workforce and culture, banks responded that implement a variety of practices and policies. The most common bank diversity and inclusion practices are shown in Table 7.

Table 7: Most Common Bank Diversity and Inclusion Practices and Policies

|

Table 7: Most Common Bank Diversity and Inclusion Practices and Policies |

|

|

Diversity and Inclusion Practice |

Total Banks with Practice |

|

Recruiting Diverse Talent |

43 |

|

Linking Diversity and Inclusion Results to Performance |

36 |

|

Creating Employee Resource Groups |

35 |

|

Connecting with Diverse Communities |

31 |

|

Creating Pathways for Diverse Talent |

31 |

|

Providing Diversity Training |

29 |

|

Using Enhanced Interview Tactics |

28 |

|

Collecting Data on Diversity Results |

10 |

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

Recruiting Diverse Talent

To connect with diverse talent, banks said they use recruiters, job banks, and job networking platforms to target diverse communities. They also reported participation in career fairs that target women and minorities for further access to diverse candidates. Banks also said they have relationships with historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and minority-serving institutions (MSIs) as a pipeline for diverse talent. For example, Ally Financial stated that it holds an annual internship program in partnership with nonprofit organizations to recruit HBCU students to compete in an entrepreneurship program for young black entrepreneurs. During this internship program, students are provided a housing and transportation stipend. Ally stated that last year it offered scholarships and full-time job offers to several students from the program.

Linking Diversity and Inclusion Results to Performance

Congressman Al Green (D-TX) Chair, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations |

“” “In my office, diversity and inclusion is more than a talking point. It's an action item. There is no shortage of diverse people and businesses for banks to hire and promote. Just a shortage of leaders, including bank leaders, with the will to make it happen.”

|

To create accountability for diversity and inclusion results, 36 of 44 banks said that they link bank employee performance measures to diversity and inclusion efforts. Although banks may interpret that performance measures are generally linked to compensation, none of the 44 banks said they tie performance measures directly to compensation. According to a 2017 report by Diversity Best Trends, “D&I efforts should be measured with the same scrutiny that other business objectives receive and include a mix of quantitative and qualitative measures to help track progress and inform improvements.” The report suggests using quantitative measures such as tracking hiring decisions and promotion rates of women, minorities and other underrepresented groups. The report also suggested that qualitative measures could include review of employee survey responses and focus groups to create a baseline and evaluate the success of diversity and inclusion measures over time.[44]

Creating Employee Resource Groups (ERG)

Although called by various names, ERGs are employer recognized groups of employees who share common concerns such as race, gender, sexual orientation, or other similarities. In March 2018, Diversity Best Practices noted that top management in some companies view their ERGs as “instrumental to the success of their business” and were a valuable asset in “recruitment and retention, marketing, brand enhancement, training, and employee development.”[45] These groups can also be a resource to women and minorities for leadership and career development as they navigate advancement barriers. Thirty-six out of the 44 responding banks mentioned forming employee resource groups, business resource groups, and employee networks. Huntington, for example, noted that ERGs add value to their company because they provide a safe space for employees to express the diverse aspects of their identity and experiences. Additionally, Capital One mentioned that ERGs help create a pipeline of diverse, qualified talent, especially for leadership roles.

Connecting with Diverse Communities

Congressman Stephen F. Lynch (D-MA) Chair, Task Force on Financial Technology |

“” “As Chair for the Task Force on Financial Technology, I am taking an in-depth look into the ways technology is changing and influencing how Americans access banking and financial services. This is especially a concern in diverse communities that may have previously been the victims of redlining, predatory and other discriminatory practices.” |

Banks acknowledged the importance of connecting to the diverse communities they serve. Twenty-two banks noted working with outside organizations dedicated to the advancement of women and minorities to enhance the diversity efforts of their organizations. For example, some banks reported connecting with the National Black MBA Association (“NBMBAA”), which is dedicated to developing partnerships that create intellectual and economic wealth in the Black community and with the Financial Services Pipeline (“FSP”) initiative in Chicago, which seeks to address the lack of diversity in the Chicago-area financial services sector. Thirteen banks partner with community groups to support the employability of overlooked and underserved communities through specific skills-based trainings such as digital marketing, analytics, and technology. For example, Barclays said it works with a community group to support low-income first-generation graduates from a local university to access high-powered digital marketing and analytics careers. Barclays also said it hosts recruiting events and employers hire graduates directly from the program.

Banks also responded that they promote diversity and inclusion externally through volunteering in diverse communities. Three banks said they established volunteer programs with annual employee goals for volunteer hours. HSBC noted that these programs allow its employees to connect to the diverse communities the bank serves. HSBC stated that it specifically focuses its volunteer work on financial literacy and economic mobility.

Creating Pathways for Diverse Talent

Congressman Emanuel Cleaver (D-MO) Chair, Subcommittee on National Security, International Development and Monetary Policy |

“” “Banks and other organizations that continue to move too slowly on diversity and inclusion initiatives may find themselves losing competitive advantage and profitability. Employees may move out of a company if they don’t see a pathway to move up.”

|

Career and leadership development through mentorships and sponsorships: Companies that have formal and informal programs can provide career guidance to and support for women and minorities as they vie for opportunities and promotions in an organization. A 2017 review of diversity programs noted that a good sponsor or mentor, with the appropriate supporting infrastructure, can help women navigate inflection points in their careers and lobby for them to receive promotions, training, and key assignments. For example, US Bancorp said it established a women’s advancement initiative to increase female representation in senior leadership by effecting change at the system and managerial levels, as well as developing women in the leadership pipeline. Part of this strategy includes providing ongoing development opportunities for women to strengthen their business, strategic, and financial acumen. Santander said it has a “returnship” program to encourage individuals to return to the workforce after a significant absence, possibly as a result of raising children, caring for a sick family member, or serving in the armed forces. Participants in the “returnship” program develop industry knowledge through hands-on, business-specific project experience, dedicated learning and development opportunities to update professional and technical skills, while receiving one-on-one support and networking opportunities.

Internships and scholarships for diverse individuals: Ally Financial reported that it hosts an entrepreneurship program in collaboration with a nonprofit college fund to select students from HBCU’s to compete in a two-and-a-half-day business competition. In this competition, students develop solutions to economic problems in various industries and then pitch to a panel of expert judges consisting of entrepreneurs, small business owners, and venture capitalists. Additionally, all participants of this program received scholarships, summer internship opportunities, and consideration for future full-time employment with Ally.

Providing Diversity Training

Banks said they provide training for staff at all levels, both voluntary and mandatory, to enhance employee awareness about diversity and inclusion issues in the workplace. For instance, 13 banks begin diversity and inclusion training for its employees at new hire orientation, and then allow employees to continue learning through voluntary diversity and inclusion training modules. Senior executives and managers can play a pivotal role in fostering a diverse and inclusive environment. In keeping with this sentiment, six banks reported that they provide additional training for senior managers in addition to other company-wide offerings. Formal training can also help identify conscious and unconscious biases and reduce the negative effects in the workplace. According to Deloitte’s 2018 review of “the diversity and inclusion revolution,” mandatory or voluntary bias and diversity training can change organizational culture and reduce biases that may have inadvertently led to negative diversity outcomes.[46] Organizations have noted that unconscious bias can negatively affect women and minorities in the workplace, limiting their opportunities to move to the senior and executive ranks and that training is required to ameliorate these issues. While many bank responses did not specify whether their unconscious bias trainings were mandatory, several mentioned requiring this training when an employee is hired. M&T Bank responded that even though it provides unconscious bias training and workshops, “unconscious bias is one of the most difficult impediments to eliminate”, and that the bank is working to “require a prolonged focus and consistent effort” to address this issue, namely through training and awareness.

Using Enhanced Interview Tactics

Building a diverse pipeline of candidates requires interview practices that attempt to eliminate bias in the process and therefore, create more opportunities for women and minorities to be considered and ultimately selected for positions and promotions.

Implementing a Rooney Rule for interviewing diverse candidates: Twelve banks said that they have implemented a “Rooney Rule” for interviewing a diverse slate of candidates, where at least one minority and/or woman must be considered for each open leadership position. Most Rooney Rule policies are modeled after a National Football League policy adopted in 2003 which requires league teams to interview minority candidates for head coaching and senior football operation positions. Wells Fargo states that they use the Rooney Rule for employee roles up to six levels down from the CEO. Similar to these initiatives, in September 2019 the House of Representatives unanimously passed H.R. 281, the “Ensuring Diverse Leadership Act.” If enacted into law, H.R. 281, also known as the “Beatty Rule,” would require that at least one representative of gender diverse, racial and ethnic diversity be considered for Federal Reserve Bank president vacancies. Outside the financial services industry, the legal profession similarly uses the “Mansfield Rule,” where the slate of candidates considered for leadership positions must include at least 30 percent women, racial or ethnic minorities, and members of the LGBTQ community.[47]

Interview guarantee for certain veterans: Hiring veterans also brings diversity to the workplace because of their specialized training. Comerica stated that it participates in the Guard and Reserve Interview Promise program, where participating companies promise to interview Guard and Reserve members who meet job opening classifications.

Interview guidelines for objective hiring: Some companies, including banks the Committee staff reviewed, have developed best practices and guidelines to successfully interview diverse candidates. To mitigate biases, these guidelines help interviewers assess candidates objectively and consistently as well as mitigate interviewer biases. To achieve interview objectivity and a consistent interview experience among candidates of varying race and gender, American Express stated that it uses behavioral-based interview guides. Additionally, the bank said it requires that all interview panels (i.e. those rating the candidate) include at least one minority and/or woman.

Tracking the diversity of candidates interviewed and hired: Citigroup stated that it has a goal of having at least 40 percent of assistant vice president through managing director roles filled by women by the end of 2021. To meet this target, Citigroup stated that it tracks how many females are currently being interviewed and applied a Rooney Rule for these type of senior level positions to better guarantee that women and minority candidates have a stronger opportunity to be considered and ultimately selected. According to BNY Mellon, business groups within that bank work with Human Resources and/or its Diversity & Inclusion staff to track diversity throughout the talent lifecycle, including hiring external talent as well as internal promotions. To the extent that diverse candidates are underrepresented, BNY Mellon reported that its Human Resources and Diversity & Inclusion staff work with business groups to ensure women and minorities are using the Rooney Rule. Huntington Bank stated that it has a scorecard for each business segment that sets an objective performance measure for workforce and supplier diversity. According to Huntington, its leadership reviews and evaluates monthly reports that show progress toward these goals and its Board of Directors receives quarterly reports regarding Huntington’s performance metrics related to diversity and inclusion.

Collecting Data on Diversity Results

As a part of a meaningful diversity and inclusion strategy, banks reported that they gather employee feedback on the implementation of their diversity and inclusion strategies. Nine banks reported that they conduct a company-wide survey to allow its employees to share opinions on what it does well and where they can improve in diversity and inclusion. Citizens Bank reported that it conducts follow-up analyses after its survey to examine any potential differences in opinions among various demographic groups.

DISCLOSING DIVERSITY DATA TO FINANCIAL REGULATORS AND THE PUBLIC

Section 342(e) of the Dodd Frank Act requires that the Offices of Minority Women and Inclusion (OMWI) submit an annual report to Congress regarding the actions taken by the respective financial services regulatory agencies and the OMWI office.[48] To fulfill this requirement, the lead prudential banking and consumer finance regulatory agencies adopted the Joint Standards for Assessing the Diversity and Policies and Practices of Entities Regulated (Joint Standards) in June 2015, which established standards for assessing a regulated entity’s diversity policies and practices.[49] However, financial regulators made compliance with the Joint Standards voluntary.

It is also important that banks and other companies publicly disclose their diversity data because it creates accountability with shareholders and the public they serve. For example, a June 2019 Industry Week article noted that “the disclosure of workplace equity data is increasing in its importance to investors and they are letting companies know that this information is material to investment decisions.”[50]

Committee Staff Findings on Disclosing Data with Financial Regulators and the Public

Banks Are Not Disclosing Diversity and Inclusion Data with Regulators and the Public

Because compliance with the Joint Standards is voluntary, participation by banks in the requested self-assessments from financial regulators has been low. Committee staff review of a sample of bank regulators’ OMWI reports reveals low response rates by requesting agency:

- FDIC – 16.7% response rate.

- OCC – 9.3% response rate.

- Federal Reserve – 5% response rate.

Banks also varied in the extent to and frequency with which they publicly disclose their diversity statistics and policies. Committee staff found that 23 of the 44 banks publicly share diversity statistics. In June 2017, Fortune Magazine also noted that even if they were ranked among the best at diversity, only three percent of Fortune 500 companies publicly share their full diversity.[51]

In lieu of banks’ and other financial services firms’ limited participation in disclosing diversity data with regulators and the public, industry organizations have created venues for their member firms to share diversity data and compare themselves against industry benchmarks for diversity and inclusion results. For example, over the past 12 years, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) offers its member firms an opportunity to participate in a biannual survey where data is collected about the member firms’ workforce and supplier diversity as well as other diversity related initiatives. Member firm data are collected by a third-party, and participating firms sign a non-disclosure agreement that data will remain confidential. Data are then aggregated, and participating members are provided an individual report that compares their summary results versus the aggregated data of all survey participants. According to SIFMA, 14 of the 44 banks the Committee staff reviewed have participated in at least one of SIFMA’s six surveys to date. SIFMA indicated to Committee staff that it continues to work with its members on a plan and format to publicly disclose its diversity survey results.

According to DiversityINC, five of the 44 banks Committee staff reviewed ranked among DiversityINC’s top 50 list in 2019, which is based on DiversityINC’s annual evaluation of corporate diversity management. This annual assessment is voluntary, free, and open to companies, including banks, with more than 1,000 employees. Companies are assessed and ranked overall on six diversity and inclusion metrics: human capital, leadership accountability, talent programs, workplace practices, supplier diversity and philanthropy. Names of companies, including banks, that participate in the assessment but do not rank among the top 50 are not publicly identified.

CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION GOALS AND INITIATIVES

Committee Findings on Banks’ Challenges in Implementing Diversity and Inclusion Goals and Initiatives:

While all the banks have expressed their commitment to diversity and inclusion, only 24 of the 44 banks provided deliberate, specific consideration of the challenges they faced regarding diversity and inclusion. The Committee asked the banks to describe any challenges they faced in implementing their diversity goals and initiatives (Question #8). The Committee staff analysis of the banks’ responses to this question revealed 17 different challenges, some of which were common across multiple banks. However, several banks did not specify any challenges. Rather, 20 banks, including seven of the eight megabanks, gave a blanket statement, expressing their institutional commitment to diversity and inclusion without providing more transparency about the underlying obstacles that prevent them from having more success with their diversity and inclusion initiatives.[52] Nonetheless, all 44 banks acknowledged in some way that they need improvement with respect to diversity and inclusion.

For those banks that described specific challenges, the two most commonly cited challenges to the implementation of diversity and inclusion goals were: the competition for diverse talent with science, technology, engineering, math (STEM), and finance related expertise and the absence of a consistent definition of diversity and inclusion. Table 8 provides a consolidated list of the banks’ responses and the corresponding number of banks to which each challenge applies.

Table 8: Banks’ Challenges to Implementing Diversity Goals and Initiatives

|

Bank Responses |

Number of Banks |

|

Competition for talent in STEM/Finance |

11 |

|

No consistent definition of diversity and inclusion |

4 |

|

Data collection/self-identification problem |

3 |

|

Geographical limitations |

3 |

|

Talent retention |

3 |

|

Streamlining/integrating diversity and inclusion across large organization |

3 |

Source: U.S. House Financial Services Committee Staff Analysis of Bank Diversity Data

Competition for Talent in STEM/Finance

Eleven banks provided responses indicating a belief that they are competing for the same small pool of diverse talent because of the lack of candidates with STEM educational background and experience. Specifically, Banks cited a need for expertise in engineering, machine learning, coding and application and software development, but said they have difficulty finding diverse candidates for those positions. GAO’s 2017 report on diversity trends in the financial services industry similarly noted that some financial services firms have cited that the financial services firms are increasingly in competition with technology firms for talent.[53] For example, in their response, TD Bank states:

Innovation is leading to a high demand for emerging skills, and we are competing for talent both inside and outside our industry for a limited pool of high-potential talent that has the expertise as well as the people skills, leadership capabilities, business breadth, and diversity sensibilities that are necessary for future leadership roles.

The banks’ affinity towards recruitment at elite institutions with limited minority enrollment and degree completion rates may also limit their ability to connect with diverse talent, especially those with STEM expertise. For example, Barclays Bank responded that it is “constrained in graduate recruiting efforts by the diversity of candidates at the schools that provide training for the skills required by the sector.” GAO’s 2017 report confirmed that financial services firms’ focus on recruiting and hiring from elite universities is a source of their diversity recruiting challenges and practices.[54] The American Council on Education determined that although African-American and Latino students enter four-year institutions and major in the STEM fields at similar rates as white and Asian-American students, their probabilities of successfully completing STEM degrees are much lower than their white and Asian American counterparts.[55] However, one study published by the American Economic Review demonstrated that underrepresented minority students are more likely to have greater success in completing a science degree and graduate in less time when they attend other non-elite colleges and universities.[56] Moreover, articles on diversity in STEM in The Atlantic and Higher Education Today noted that such “non-elite” colleges, including some public universities and HBCUs, provide intentional and rigorous academic support to minority students pursuing STEM degrees. Further, these institutions have highly acclaimed success in graduating underrepresented minority students with STEM degrees.[57] A 2014 National Science Foundation report concluded that nearly 30 percent of Black students who earned doctorates in science and engineering receive their bachelor’s degrees from HBCUs.[58]

Even though elite colleges may have strong academic reputations, there is no empirical evidence that these colleges necessarily provide a higher quality education. In 2018, an article in The Atlantic on college selection affirmed research that attending an elite college is not a predictor of a graduate’s success. Rather, those who attend the elite colleges and universities reap the benefits of the alumni networks and signaling effects.[59] Therefore, one way banks can avert their STEM diversity pool challenge is by targeting their recruitment at colleges and universities that have notable graduation and success rates for minorities in STEM.

No Consistent Definition of Diversity and Inclusion

Four financial institutions indicated that either the lack of a standard and/or constantly evolving definition of diversity and inclusion posed challenges in implementing their diversity initiatives. For example, TD Bank remarked, “Rather than focusing on one area of identity, employees are increasingly interested in intersectionality, where an individual identifies with more than one area of diversity, and more value is placed on equality and/or parity.” Other institutions listed the continuing need to evaluate and adapt to the evolving definition of diversity and inclusion in a constantly changing work environment as a challenge. Commonly, diversity has referred to underrepresented race and gender demographics. For example, a National Public Radio report on workplace diversity noted that while diversity has historically referred to categories like race and gender, companies and diversity experts continue to broaden the pool and audience to which diversity applies by adding categories such as age, sexual preference, disabilities, and weight. Though the definition of diversity and inclusion has not remained static, EEOC has a standard set of demographic categories that banks could use. EEOC requires certain companies to complete an annual survey on employee data, including voluntary, self-identified race and ethnicity data. Moreover, EEOC provides definitions for race and other employee data to create general consistency in their survey response.

Data Collection/Self-Identification Problem

Three banks remarked that difficulties collecting reliable demographic data, which are the basis for metrics that measure the success of diversity and inclusion programs and initiatives, imposed a challenge. Specifically, these banks said that even though employees and applicants have the option to self-identity their demographic details, many employees may choose not to disclose. Other institutions tied the lack of a standard and consistent definition of diversity and inclusion to their data collection challenges. For example, SVB commented, “because there is no standard set of definitions for diversity categories and other diversity-related terms, reporting and aggregating of diversity data may be inconsistent.”

Geographical Limitations

Three banks stated that the lack of diversity within their geographic regions made it difficult to recruit and hire diverse talent. For example, PNC pointed to a regional talent gap, noting the overall low proportion of high school students within its geography that go on to pursue post-secondary education opportunities. To address this challenge, PNC said it partners with local high schools and community organizations to implement developmental educational programs. PNC said that minority candidates expressed preferences to live in more diverse, urban communities.

Talent Retention

Three banks highlighted that even though they have had some success recruiting and hiring diverse employees, retention of their diverse employee was difficult. However, two of these firms, also referenced development and management programs that they believed will support and help retain diverse employees. Research also supports this practice. For example, Diversity Best Practices noted that top management in some companies view their employee resource groups as “instrumental to the success of their business” and were a valuable asset in “recruitment and retention, marketing, brand enhancement, training, and employee development.”[60] Professional affinity groups can also be a resource to women and minorities for leadership and career development as they navigate advancement barriers.

Streamlining Diversity and Inclusion

Three banks indicated that streamlining and integrating diversity and inclusion across a large organization was a challenge. One bank attributed this challenge to having multiple departments across several locations. Whereas, two other banks associated this challenge with recent institutional and structural changes. For example, Santander Bank noted that it had recently moved its U.S. entities under Santander Holdings, U.S.A., a subsidiary of Banco Santander, S.A.

Other Challenges Reported by Banks

The banks cited other challenges including:

- Difficulties in identifying and enforcing behaviors that support diversity and inclusion;

- Unconscious bias, negative perceptions of the industry;

- A lack of qualified diverse suppliers;

- Lack of diversity in post graduate education;

- Evolving regulatory requirements;

- Lateral hiring;

- Additional time and resources that are required for diverse recruiting;

- Lack of brand recognition;

- Negative perceptions of the industry; and,

- Collection of data on suppliers.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO IMPROVE DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION AT AMERICA’S LARGEST BANKS

America’s largest banks conceded, and Committee staff findings validate, that more work is needed to improve their diversity and inclusion results. To increase their diversity, banks must ensure they are tracking the levels of underrepresented groups in their workforce, suppliers and boardrooms. Disclosing that data to regulators and the public will create accountability for the diversity and inclusion goals that banks assert they are committed to.

Based on the findings noted in this report, additional recommendations include the following:

Banks Must Disclose Diversity Data with Regulators and the Public

The Financial Service Committee should consider legislation to require banks, other financial services firms, and all companies under the Committee’s jurisdiction to respond to diversity data requests from the Offices of Minority and Women and Inclusion at their respective regulators and make their full reports available to the public. In a November 2019 hearing, the Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Financial Institutions considered several pieces of legislation that would require banks to disclose diversity legislation, including:

- H.R.___ Mergers and Acquisition Disclosure of Diversity and Inclusion Act (Cleaver). The draft bill would require banks subject to a merger or acquisition to include diversity and inclusion data with their merger application.

- H.R.___ Promoting Diversity and Inclusion in Banking Act. The draft bill would require bank examinations of diversity and inclusion efforts, including policies to promote diversity and inclusion, and it would require responses to Office of Women and Minority Inclusion (OMWI) assessments of diversity policies and practices.

Banks Must Track and Increase Spending and Investment with Diverse Suppliers and Asset Managers

The Financial Services Committee should consider legislation that creates opportunities for women- and minority- owned firms to be considered, and ultimately chosen, as suppliers, vendors, and asset managers. Unfortunately, Committee staff found that some banks are still not tracking what they spend and invest with diverse businesses. Without tracking, banks will have no way to measure where they are with diverse spending or future increases. Moreover, despite evidence that many of these firms achieve results as good as or better than their industry counterparts, banks and others continue to exhibit bias against diverse owned firms. Banks and other financial services firms should take advantage of opportunities to increase and expand their relationships with diverse suppliers and diverse asset managers, where applicable and appropriate for their mutual success. When new supplier or investment opportunities arise, banks and other financial services firms should make it a practice to give serious consideration to at least one diverse firm when contracting for procurement, investment management, or other services. During a June 2019 Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion hearing on diverse asset managers, lawmakers discussed requiring investors to consider diverse-owned firms when launching new funds for management.

Banks Must Increase and Disclose Bank Board Diversity

Banks and other financial services firms should disclose to regulators and the public the diversity of their corporate boards. Disclosure creates accountability. Institutional investors, including banks, also have the power to influence diversity and inclusion by requiring the firms they do business with to have diverse boards. In November 2019, the Improving Corporate Governance Through Diversity Act of 2019 (H. R. 5084), passed the House of Representatives. If enacted, public companies would be required to annually disclose in their proxy statements, based on voluntary, self-identification, the gender, racial and ethnic composition of their board of directors, nominees to the board of directors, and executive officers. Banks can also create accountability by requiring firms that they do business with to enhance their board diversity and governance. For example, Forbes reported that the Goldman Sachs’ CEO said the investment bank “will only take companies public if they have at least one “diverse” board member, with a focus on women.”[61]

APPENDIX I

Bank Diversity Data Request Letter

APPENDIX II

Methodology

Summary of Diversity Data Request

Chairwoman Waters and Chair Beatty asked bank holding companies and savings and loan holding companies with assets over $50 billion (44 total) to comment on their diversity and inclusion data and practices. While the request was directed at bank holding companies and savings and loan holding companies with at least $50 billion in total assets based on publicly available information from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) at the time of the request,[62] the responses the Committee received from institutions generally focused on their depository institutions, and those vary in size. The request solicited a mix of quantitative and qualitative responses and deliberately did not include a template for banks to report information. Rather, banks were given an opportunity to define what diversity means to their respective institutions. Banks were also encouraged contact Committee staff for clarification on the request and to provide updates on their diversity and inclusion initiatives implemented since or not included in their original responses. Selected bank examples are included in this report, as appropriate.

All 44 banks responded to Chairwoman Waters’ and Chair Beatty’s request for information. Committee staff then analyzed the content of the financial institutions’ responses to develop descriptive statistics and conclusions. Qualitative responses were also analyzed by Committee staff to identify common themes among bank diversity and inclusion practices as well as highlight common challenges to implementing diversity initiatives.

Limitations on Scope of Analysis

The Committee requested historical data on banks’ diversity and inclusion policies and practices from 2015 to present. Trend analyses could have revealed underlying causes such as how the gender pay equity ratio has evolved over time for individual banks and the industry since the implementation of Section 342(b) of Dodd-Frank. Unfortunately, none of the banks provided responses for all questions or all years requested to inform a robust trend analysis.

APPENDIX III

Definitions

GENDER: For the purposes of this analysis, gender is treated as binary (male/female). “Male” and “Female” are defined at the discretion of the bank, though many banks indicated that this was self-reported information. If the bank reported on the number of employees that identify as non-binary, a third gender, or declines to identify, that figure is accounted for in the total number of employees and is not included in any counts or estimated counts of male or female employees in this analysis.

MEGABANK: A financial institution is a “megabank” if it fulfills the criteria for a global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) as developed by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in its November 2019 report and are subject to the G-SIB capital surcharge under existing U.S. regulatory action.[63] For the purposes of this analysis, the report labels the following US-based banks as megabanks:

- Bank of America

- BNY Mellon

- J.P. Morgan

- Citigroup

- Goldman Sachs

- Morgan Stanley

- State Street

- Wells Fargo

This is in line with how the Committee has previously defined “megabanks” using the FSB’s G-SIB criteria and how they are defined in reference to U.S. regulations.[64]

OTHER LARGE BANKS: 36 banks that that the committee reviewed that are not classified as megabanks

RACE/ETHNICITY: Totals for the number of employees in each racial/ethnic category was defined at the banks’ discretion, though many banks indicated that this was self-reported information. For the purposes of this analysis, the following racial/ethnic categories were used:

White: Employees identifying as “White” and not of Hispanic descent;

Black: Employees identifying as “Black” or “African American;”

Latino: Employees identifying as “Latino,” “Hispanic,” and “Hispanic descent;”

Asian: Employees identifying their ethnicity as “Chinese-American” “Korean-American” “Japanese-American” “Filipino-American” “Middle Eastern” “South East Asian” and “Indian-American;”

Native American: Employees identifying as “Native Hawaiian” and “Native Alaskan;”

Pacific Islander: Employees identifying as “Native Hawaiian” are not included under this definition of “Pacific Islander;”

Other/Not Specified/Two or More: Employees identifying as one or more races or ethnicities;

Diverse/Diverse-owned: “Diverse” was defined at the banks’ discretion, though many institutions define “diversity” as belonging to any of these groups, including racial/ethnic minorities, women, veterans, LGBTQ+ individuals, persons with disabilities or other protected classes;

Women-owned: “Women-owned” was defined at the banks’ discretion, though it generally means majority (<50 percent) female-identifying ownership; and

Minority-owned: “Minority” was defined at the banks’ discretion. Many banks defined “minority” as majority ownership by a person belonging to racial/ethnic minority group. Report analyses note any instances where the definition of “minority” included veterans, persons with disabilities or persons belonging to other protected classes.

###

_______________________________

[1] Vivian Hunt, Dennis Layton, and Sarah Prince, “Why Diversity Matters,” McKinsey & Company, January 2015.

[2] Matt Krentz, “Survey: What Diversity and Inclusion Policies Do Employees Actually Want?” Harvard Business Review, February 05, 2019,

https://hbr.org/2019/02/survey-what-diversity-and-inclusion-policies-do-employees-actually-want.

[3] Sylvia Ann Hewlett, Melinda Marshall, and Laura Sherbin, How Diversity Can Drive Innovation, Harvard Business Review, December 2013,

https://hbr.org/2013/12/how-diversity-can-drive-innovation.

[4] Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act 12 U.S.C. § 5452 (2010).

[5] Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act 12 U.S.C. § 5452(e) (2010).

[6] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC); Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve); Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC); National Credit Union Administration (NCUA); Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB); and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). “Final Interagency Policy Statement Establishing Joint Standards for Assessing the Diversity Policies and Practices of Entities Regulated by the Agencies,” Federal Register (June 10, 2015.)

[7] Congresswoman Joyce Beatty to Offices of Minority, Women and Inclusion, March 28, 2019.

[8] Banks are listed in descending order of asset size.

[9] Era Dabla-Norris and Kalpana Kochhar, “Closing the Gender Gap,” International Monetary Fund (March 2019),

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2019/03/closing-the-gender-gap-dabla.htm.

[10] Vivian Hunt, et. al. “Delivering through Diversity,” McKinsey & Company (January 2018),

https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity.

[11] Emily Flitter, “This Is What Racism Sounds Like in the Banking Industry,” New York Times, December 14, 2019,

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/11/business/jpmorgan-banking-racism.html.

[12] Government Accountability Office. “Financial Services Industry Trends in Management Representation of Minorities and Women and Diversity Practices, 2007-2015,” GAO-18-64 (November 8, 2017).GAO-18-64, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-64.

[13] US Congress. House. Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion. Hearing on “Promoting Inclusion: Examining the Need for Diversity Practices for America’s Changing Workforce.” October 17, 2019,/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=404483.

[14] Bernard Guinyard, Director of Diversity and Inclusion, United States. Cong. House. Committee on Financial Services. Hearing on Promoting Inclusion: examining the Need for Diversity Practices for America’s Changing Workforce October 17, 2019. 116th Cong. 1st sess. statement Bernard Guinyard, Director of Diversity and Inclusion, Goodwin). https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/hhrg-116-ba13-wstate-guinyardb-20191017.pdf.

[15]Committee staff was able to aggregate the 2018 demographic data for 34 of 44 respondents and about two-thirds of the respondents for years 2015 through 2017. Only 21 banks provided total work force demographic data for a 2019 as of date. Hence, this report focuses on an analysis on data provided from 2015 through 2018. Other banks disaggregated these data by career level, which are discussed separately.

[16]Other* in Figure 1 refers to employees that self-identified as other, two or more, or did not specify. Committee staff acknowledge that that these figures are not exact due to reporting errors. For example, the total racial breakout for some banks did not equate to their total number of employees.

[17] Due to data reporting anomalies this report is only able to aggregate and compare the demographics of 5 megabanks to 29 large banks.

[18] Huntington provided a combined percentage for women and all racial ethnic minorities.

[19] House Committee on Financial Services. " Waters Convenes Hearing on Need for Diversity on Federal and Corporate Boards." House Committee on Financial Services press release, June 20, 2019,/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=403959.

[20] U.S. Congress. House Committee on Financial Services. Hearing on Diversity in the Boardroom: Examining Proposals to Increase the Diversity of America’s Boards, Committee Memorandum. 116th Cong., 1st sess., 2019.

[21] T. Rowe Price Group, “Proxy Voting Guidelines,” T. Rowe Price Website, 2018.

[22] Deloitte, “Seeing is believing: 2017 board diversity survey,” 2017.

[23] Ann L. Owen and Judit Temesvary, “Gender Diversity on Bank Board of Directors and Performance,” FEDS Notes, February 12, 2019.

[24] Ibid.

[25] U.S. Congress. House Committee on Financial Services. Hearing on Diversity in the Boardroom: Examining Proposals to Increase the Diversity of America’s Boards, Hearing Graphic. 116th Cong., 1st sess., 2019, /calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=403834.

[26] Barclays does not include any mention of the race/ethnicity of its directors.

[27] BMO stated that 45% of their external directors are women and/or persons of color but does not provide disaggregated data on the number of women and the number of persons of color.

[28] Charles Schwab does not include any mention of the gender or the race/ethnicity of its directors.

[29] National Minority Supplier Development Council, “The Business Case for Minority Business Enterprises: Fueling Economic Growth,” accessed February 6, 2020, https://www.nmsdc.org/wp-content/uploads/v3Alt-Wht-8.5-x11-Single.pdf.

[30] “The NGLCC Founding Story,” accessed February 6, 2020,https://www.nglcc.org/who-we-are/nglcc-story.

[31] Billion Dollar Roundtable accessed February 6, 2020,https://www.billiondollarroundtable.org/.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Heather McCulloch, “Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap—What it is, Why it Matters and What Can Be Done About It,” January 2017.

[34] Ibid.

[35]Nick Noel, D. Pinder, S. Stewart III, and J. Wright. “The economic impact of closing the racial wealth gap” McKinsey. August 2019.

[36] US Congress. House. Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion. Hearing on “Examining the Racial and Gender Wealth Gap in America.” September 24, 2019. U.S. Congress. 116th Cong., 1st session, /calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=404344.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Josh Lerner, et. al. “Diverse Asset Management Project Firm Assessment,” Bella Research Group, May 2017.

[39] US Congress. House. Committee on Financial Service. Hearing on “An Examination of Facebook and Its Impact on the Financial Services and Housing Sectors.” October 23, 2019. U.S. Congress. 116th Cong., 1st sess., /calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=404487.

[40] U.S. Congress. House. Diverse Asset Managers Act. HR ____. 116th Cong., 1st sess., /uploadedfiles/bills-116pih-divassmgr.pdf.

[41] U.S. Congress. House. Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion. Hearing on “Diverse Asset Managers: Challenges, Solutions and Opportunities for Inclusion.” 116th Cong., 1st sess. June 25, 2019, /calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=403836.

[42] ETRADE, Goldman Sachs, and MUFG state in their respective letters that they do not track investments with diverse asset management firms. Discover states that they do not invest with or through vendors and asset managers as part of its core businesses.

[43] Because of the variance in the type of data banks provided, many of the responses were not able to be used for averages, trends, or other calculations.

[44] Diversity Best Practices, “Linking D&I to Compensation and Bonus,” November 26, 2018, https://www.diversitybestpractices.com/sites/diversitybestpractices.com/files/attachments/2018/11/linking_di_to_compensation.pdf.

[45] Diversity Best Practices. “Diversity Best Practices Employee Resource Groups, last modified March 6, 2018,

https://www.diversitybestpractices.com/employee-resource-groups.

[46] Juliet Bourke and Bernadette Dillon. “The diversity and inclusion revolution: Eight powerful truths” Deloitte Insights, Deloitte, accessed December 18.

[47] Diversity Lab. “102 Law Firms Sign On to Mansfield Rule 3.0,” last modified September 3,2019,https://www.diversitylab.com/pilot-projects/mansfield-rule-3-0/.

[48] Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act 12 U.S.C. § 5452 (2010).

[49] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC); Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board); Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC); National Credit Union Administration (NCUA); Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB); and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). “Final Interagency Policy Statement Establishing Joint Standards for Assessing the Diversity Policies and Practices of Entities Regulated by the Agencies,” Federal Register (June 10, 2015.)

[50] Industry Week Staff, “Investors Representing $1.61 Trillion in Assets Tell Companies to Disclose Workplace Equity Data,” Industry Week, June 19, 2019.

[51] Grace Donnelly, “Only 3% Of Fortune 500 Companies Share Full Diversity Data, “ Fortune, June 7, 2017, https://fortune.com/2017/06/07/fortune-500-diversity/.

[52] Bank of America Corporation, Bank of New York Mellon Corporation, BB&T Corporation, BBVA Compass Bancshares, Inc., BNP Paribas USA, Inc., Citigroup Inc., Citizens Financial Group, Inc., E*TRADE Financial Corporation, Fifth Third Bank, Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., Huntington Bancshares Inc., Morgan Stanley, Northern Trust Corporation, RBC US Corporation, Regions Financial Corporation, State Street Corporation. SunTrust Banks, Inc., Synchrony Financial, Teachers Insurance & Annuity Association of America, Wells Fargo & Company.

[53] Government Accountability Office. “Financial Services Industry Trends in Management Representation of Minorities and Women and Diversity Practices, 2007-2015,” GAO-18-64 (November 8, 2017).GAO-18-64, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-64.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Eugene Anderson and Dongbin Kim, “Increasing the Success of Minority Students in Science and Technology”. American Council on Education, The Unfinished Agenda: Ensuring Success for Students of Color (March 2006), https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Increasing-the-Success-of-Minority-Students-in-Science-and-Technology-2006.pdf.